Table of Contents

Training is hard — not just in the physical sense, but also when it comes to knowing what to actually do in the gym.

There are a lot of variables to account for (especially in relation to nutrition), and the principles of proper training tend to be complex and intimidating to those without an exercise science degree. Even for those with an exercise science degree (like me!) this stuff can still be super complicated at times, leading to decision paralysis, confusion and doubt.

So I’ve tried to condense as much knowledge as I could into this article, with the hopes that it can give you more confidence in the gym, guide you in the right direction with your training, and act as a much-needed template that I can fall back on in my own times of uncertainty.

Terms to Know

Hypertrophy- The process of muscle growth (closely related to the concept of anabolism).

Atrophy- The process of muscle loss/breakdown (closely related to the concept of catabolism).

Repetition (Rep) - One complete cycle of a full range-of-motion, from starting-point to end-point and then back to the start.

Set - A grouping of reps, typically inferred as being unbroken.

% of RM (i.e., 1RM) - This refers to the percentage of your one rep max (RM) on an exercise or how much weight you can perform for a single rep at max effort with perfect technique. For example, 70% of a 1RM of 100lbs would be 70lbs. We can also expand to 2RM, 3RM, etc., which would follow the same stipulations for the higher rep max.

Personal Record (PR) - This refers to your best effort on a particular exercise. We can track this in terms of reps achieved with a given weight. We can also summate this over multiple sets which are referred to as volume PRs.

AMRAP - As Many Reps As Possible

ALAP - As Long As Possible

Training Week - The amount of time it takes to complete one full cycle of training sessions and prescribed rest. This is also commonly referred to as a microcycle.

Volume - A measure of total work done. This is typically tracked as sets per session or sets per training week.

Intensity - This can be defined multiple ways, but for our purposes, we will use intensity to mean how close to technical failure a set is taken, as measured by RIR or RPE.

Frequency - A measure of how many times a specific lift or muscle group is trained during a period of time, typically within a microcycle.

Mind Muscle Connection (MMC) - The ability of the nervous system to efficiently and effectively recruit the desired muscle(s). This often is present as a sensation of “feeling” the muscular contraction during a rep.

Mobility - The active ability of a joint or structure to control a range of motion (ROM) and exert strength in that range.

Flexibility - The passive ability of a muscle to go through a ROM.

Eccentric - The lengthening phase of a muscular action when the muscle fibers are under tension and being stretched. For example, during the downward phase of a squat or lowering the barbell to your chest in a bench press.

Concentric - The shortening phase of a muscular action when the muscle fibers contract and generate active force. For example, standing up out of the bottom of a squat or pressing the barbell up in a bench press.

Progressive Overload - The gradual increase in stressors — generally through more load and/or more reps — placed upon the body during training. Some form of PO is essential for consistent and continuous strength acquisition and hypertrophy.

Time Under Tension (TUT) - The total duration of time that a muscle is being strained during a set, whether continous or otherwise. While the causal relationship between TUT and hypertrophy is somewhat dubious, it is still a useful variable to understand in its application to training.

Beginner/Novice - An individual who can make consistent progress through relatively minimal effort and/or attention to the intricacies of programming and nutrition. Typically, beginners are also characterized by a lack of technical aptitude on most, if not all, movements in the gym, and an inability to push themselves close to failure/strain.

Intermediate - An individual who can still make solid progress, but the rate and magnitude of gain is more dependent on a structure/planning with both training and diet. Intermediates generally have a solid grasp of technique on most movements and can push themselves close to failure without said technique faltering.

Advanced - An individual who must follow an individualized, near-optimal plan with a high level of adherence to allow for progress to be made. Advanced athletes are proficient on ALL variations of exercise selection and can take sets to, and beyond, failure without any breakdowns.

Deciphering Training Concepts

What makes up the prescription of an exercise isn’t just the name of the variation, sets, and reps. Despite these lazy attempts that pass themselves off as “programming”, there is so much additional information that can be communicated through the effective use of training concepts.

The key is in the way the program manages these variables and how the trainee is able to interpret what is being asked of them. In other words, each must always be on the same page.

Exercise Order

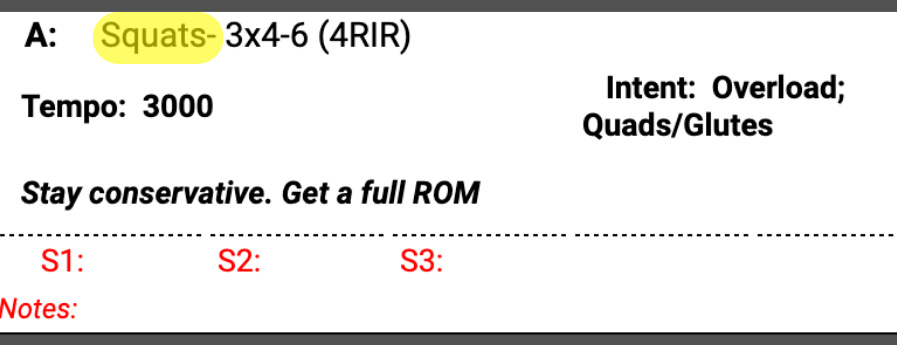

The sequence of exercises within a training day will be dictated by alphabetical order with the letter being placed to the left of the exercise name and parameters thereafter:

A: Squats 2x8-10

B: RDLs 4x10-12

Supersets, tri-sets, giant sets, and circuits, are indicated by a matching letter proceeded by numbers indicating the sequence intended to be followed:

A1: Leg extensions 2x15-20

A2: Lying hamstring curls 2x15-20

Exercise Selection

The name of the exercise should always be explicit and provide as much information as possible upfront. For example, Squats could be expanded into Heel Elevated High Bar Squats to immediately communicate relevant cues for the intended set-up and execution.

There will be certain exercises where very little can be discerned from the name alone. In these instances, it’s always best to check out YouTube for demos/tutorials or reach out to whoever created your program for more guidance.

Set/Rep Prescription

In our programs, A x B will always mean SETS x REPS and it will never be written any other way. For example, ”3x10” is 3 sets of 10 reps, and “4x5” is 4 sets of 5 reps.

The prescriptions you see for each exercise do NOT include warm-up and feeder sets. The sets leading up to your prescribed working sets should only serve to get blood into the required muscles and prepare you to perform but will not count towards accumulated volume.

Tempo

Tempo refers to the speed you perform each rep of an exercise. We can break tempo down into four components: the eccentric, the pause in the stretch, the concentric, and the pause in contraction.

The eccentric, or “negative,” portion of a lift is when you are resisting gravity. In the case of a the bench press, this is when you are lowering the bar to your chest in a controlled manner.

The pause in the stretch (transition from eccentric to concentric) will be when your working muscles are most lengthened in the end point of the eccentric. This is a place where pauses are commonly placed to increase the intensity, forcing the muscles to overcome inertia and avoid reliance on the stretch reflex. With the bench press, the pause would be incorporated when the bar is touching your chest (or at the lowest point in the ROM).

The concentric, or “positive,” phase is where you are actively lifting the weight and moving it through space. With the bench press, this would correspond to pushing the barbell off your chest.

The pause in contraction ( transition from concentric to eccentric) will be when your working muscles are most shortened in the end point of the concentric. This is another place where pauses are commonly added to increase intensity by forcing the muscles to statically contract and generate more time under tension (TUT). This would be at the top of a bench press where your arms are locked out.

It is important to note that even though a tempo is dictated in a specific way, control of the ROM and optimal execution are always superseding. If slowing the tempo even more will allow us to perform better and limit risk of injury, that is encouraged!

Tempo can be written in shorthand using a sequence of 4 numbers that each refer to a respective portion of the range of motion (ROM).

For example, 4101 would translate as “4 second eccentric, 1 second pause in the stretch, powerful concentric, and 1 second pause in the contraction.”

2000 is our default/standard tempo for hypertrophy training.

Some movements will not have a defined tempo (e.g. walking lunges, plyometrics, isometrics, etc) but the basic standards of rep-execution should always be present.

Rest Periods

Generally, we recommend taking as much time between sets as needed until you are fully recovered from your prior effort and are ready to again perform at your best.

This full rest can be anywhere from 2-5 minutes (for heavy, intense, overload-focused sets) and 1-3 minutes (for lighter and more metabolically focused work). A good rule of thumb is to make sure your heart rate and respiration have returned close to baseline before your next set, but also do not stall to the point where you lose momentum from the previous set.

There may be times where rest periods are specified explicitly in your training with the intention of bringing about a desire effect. Make note when this occurs because it will inherently affect the load you will be capable of using.

Intent

All exercises programmed are specifically aligned to the training quality we are trying to achieve, as well as the muscle(s) or movement we want to prioritize.

The primary qualities you’ll need to know will be:

Overload: Aim to progress by increasing load and/or reps achieved.

Metabolic Stress: Aim to progress by generating greater pumps and “burning” sensations.

Mind Muscle Connection (MMC): Aim to progress by increasing strength of contractions in target muscle(s).

Mobility: Aim to progress by increasing range of motion (ROM) and strength in those ranges.

Stability: Aim to progress by increasing proprioception, synchronicity, and coordination.

Strength: Aim to progress by improving effiency and technical proficiency for the intended movement. Overload is implied with a focus on Strength.

Recommendations, Cues, and Details

This is where all additional relevant information that wasn’t already made explicit will be expanded upon and explained. Many of these programming notes will be catered towards the individual trainee and their needs. It’s absolutely crucial that you pay attention to what is dictated here; it will often be necessary for getting the desired effects of the exercise and setting yourself up for success in subsequent weeks.

Range of Motion (ROM)

We strongly recommend using a full range of motion on all movements unless otherwise stated. A full range of motion is the maximum degree of movement that a joint can experience based on the mobility and flexibility of the structures around it.

However, for those who have mobility and flexibility limitations, there are common ways in which we can implement subtle changes to the set-up and execution of a movement to safely increase the ROM.

Example applications of ROM alterations:

Elevating heels during squat/leg press/lunge patterns for less mobility demands on the ankles, which leads to increased ROM and torque at the knee joint.

Adding a deficit (or elevation) to extend the ROM past the artificial limitations of the ground/floor, such as in deadlifts, rows, and split squats.

Utilizing dumbbells (DBs) more frequently to allow access to ROMs that are limited by the barbell. Some common instances where this would be applicable are in DB presses, bicep curls, and triceps extensions.

Incorporating more unilateral movements to increase ROM, provided stability and balance are not limitations. For example, split squats, single leg presses, and single arm overhead press.

Conversely, restricting ROM may occasionally be programmed or advised such as:

Overloading muscles in a more specific range

Romanian deadlifts and pronated rack pull-ups

Building up a weak point in a specific lift

Pin presses, rack pulls, and dead-stop leg presses

Working around injury

Box squats for poor knees / hips, floor press for poor elbows / shoulders

Mobility restrictions

Block pulls for poor hamstring flexibility, squat to high box for poor hip / ankle mobility

Failure and Intensity

Before we attempt to manipulate intensity as a variable in training, we first should define what failure actually is. I like to break it down into three stages: technical failure, concentric failure, and eccentric failure.

Types of Failure

Technical Failure

When you hit a technical failure, you did not fail to complete a full rep, but you will not be able to do another with proper form. This will obviously be a best guess since you cannot know if you are going to fail the next rep unless you try it, but as you gain experience, you will quickly learn to gauge the difference between technical failure and other types of failure.

Most of our exercise prescriptions refer to this definition of failure.

Concentric Failure

Concentric failure is the point in which the target muscle(s) can no longer move the external load, irregardless of technique or safety precautions. This is what most people think of when they hear “failure”, but it’s often not the best target to shoot for when taking risk, fatigue, and sustained performance into account.

Eccentric Failure

Whereas concentric failure is the inability in the muscle fibers to shorten, eccentric failure is the inability to resist lengthening under load. Eccentric failure is rarely going to be a goal in normal training, but it’s important to define in order to complete the picture of types of failure.

Modulators of Intensity

Reps in Reserve (RIR)

Many of the sets you perform will be prescribed an RIR, which is simply a way of specifying how close to technical failure we want you to take a set.

0RIR would be the same thing as technical failure (i.e., you didn’t fail any reps but you had nothing left in the tank). We will mostly live between 1-4RIR as anything further than 4RIR is not sufficiently stimulatory for hypertrophy, and 0RIR is reserved for very specific situations.

Rate of Perceievd Exertion (RPE)

In conjunction with RIR, sometimes we will use RPE. While RIR is an objective and quantitative measure of proximity to failure, RPE is subjective and qualitative (based off of how hard it feels compared to the set’s true difficulty in a vacuum).

RPE is typically measured on a scale of 1-10, but we will mostly live in 6-9RPE range as anything less would be considered a warm-up and anything more (e.g. 10+) would be a set to technical failure or beyond.

*Note: We always recommend beginning a new training program with caution and erring on the conservative side with load and intensity. Pushing too hard too quickly can lead to unnecessary muscle damage, recovery decrements, and suppressed effectiveness of subsequent training.

Warming-Up and Cooling Down

General Warm-Ups

A general warm-up is a way to systemically prepare your entire body for the impending training. Generally, this will include 5-10 minutes of low-intensity cardio, soft tissue manipulation (i.e., foam rolling), and any specific mobility/activation drills performed for the muscle group that is about to be trained.

During this period, we are looking to increase our core body temperature, increase psychological readiness, increase neural output, and decrease risk of injury without generating unproductive fatigue.

Specific Warm-Ups

A specific warm-up will constitute any work that bridges the gap between the general warm-up and the working sets.

This may be present in your program as neurologically based movements, such as single leg hip thrusts before RDLs, or even pre-exhausting movements before your first heavy compound exercises, like leg extensions before hack squats.

Be careful with overuse of Specific Warm-Ups, as doing so can negatively impact your performance by the time you get into your working sets.

Feeder Sets

Feeder sets are a subset of the specific warm-up and will be done with the intention of performing the MINIMUM amount of work possible to perform at your best on your working sets.

For example, when working up to a top set of 200x5 on squats, you may perform the following as feeder sets:

45x12

95x8

135x5

165x2

185x1

The heavier the weight being used, the more feeder sets that will be required. As you progress through your training session, feeder sets can be significantly reduced in exercises targeting common muscles and patterns.

Warm-Up Sets

Warm-Up sets are a subset of the specific warm-up and will be done with the intention of accumulating low-threshold volume before your working set(s).

Going with the same example here when building up to a top set of 200x5 on squats, you may perform the following as warm-up sets:

45x15

95x12

135x8

155x5

170x5

180x5

190x5

This will be used much more sparingly than feeder sets since our goal should be to utilize the majority of our volume on the stimulating reps of working sets. However, warm-up sets can be beneficial (and preferred) in select instances.

Cooling Down

After completing your training session, it’s highly recommended that you finish with a structured Cool Down.

Similar to the General Warm Up to begin the session, the Cool Down will have a general (~5 min of Light Cardio) and specific (~5 min of Static/Dynamic Stretching) component — only the order should be flip-flopped here to more effectively transition out of intense training.

The Static/Dynamic Stretching should consist of many of the same exercises/movements as the Mobility/Activation Drills in the Warm-Up. We use the same exercises due to the high degree of crossover in application, but the intent and execution should differ depending on where they are being performed (before or after the session). Rather than priming your mind and body to perform, here we are going to prioritize moving the accumulated byproducts of contraction out of the muscles as well as work on improving mobility/flexibility while the tissues are still “warm”.

The Light Cardio should truly be just that — light and low intensity. It is meant to promote systemic blood-flow and a “soft-landing” as your body returns to a parasympathetic (relaxed) state.

In sum, the Cool Down should append your training session to kickstart the recovery process.

Biofeedback

As a serious trainee, it is highly advised that you keep track of your biofeedback markers. These will be qualitative measures of your performance that provide more context to the session and can be leaned into when making future decisions on programming.

You can track whatever markers you find relevant to you in whichever way is most useful, but here is how we do it with our clients.

For ease, we use a 1 (worst) to 5 (best) scale for each biofeedback marker. For completeness, we recommend leaving a quick, contextual note in the margin next to the ranking (especially for those that are unusually high or low).

Completion Time - How long did your workout take from start to finish, in minutes?

Energy - How energetic were you for your lift and how did it persist throughout the session?

Strength - How was your ability to move heavy weights at high intensities? Did you set a personal record (PR) or did you feel capable of doing so if given the opportunity?

Endurance - How was your ability to sustain your strength and output over the duration of the session?

Pump - How strong was the sensation of muscular swelling after completion of a set? Could you feel your target muscle(s) pressing against the skin? Was there any degree of vascularity present?

Mind Muscle Connection - How strong was your perception of contraction? Could you feel your target muscle(s) working throughout the rep/set?

Focus - How was your ability to zone into your workout and avoid distractions?

Preparedness - How was your nutrition/sleep/stress management leading into the session? Did you review your training beforehand? Did you make sure to have the necessities to perform at your best?

Injury - How limited were you by aches/pains? Were any of the exercises causing you discomfort?

Soreness - How sore were you from the session? What specific muscle(s) experienced the soreness? (Note: Fill this out retroactively according to the peak soreness experienced from the session.)

The goal with consistently logging your biofeedback isn’t just to quantify that which is qualitative — it’s also a great way to force you to pay attention to the signals your body is providing. The way your body feels in the moment isn’t always the conclusive evidence of bad (or good) that some like to believe it is, but it is additional information that can be used to improve our decision making. And more useful information is always a good thing.

Progression Models

Progression models are how we’re going to induce adaptations to happen reliably over long periods of time. There are MANY ways to approach progression in training (as well as many ways to define it), but we will primarily use some form of the given progression models: linear, double, triple, volume, technical, and neurological.

Linear Progression

The goal is to increase weight each week.

For example, the program calls for Squats 3x8-12:

Week 1:

Set 1 – 100x10; Set 2 – 100x9; Set 3 – 100x8

Week 2:

Set 1 – 105x10; Set 2 – 105x9; Set 3 – 105x8

Week 3:

Set 1 – 110x10; Set 2 – 110x9; Set 3 – 110x8

Typically, this would be followed until you are not able to match the previous weeks’ reps achieved OR until reps start to fall out of rep range. It is important to start progression more conservatively here, to allow for increases over subsequent weeks.

Double Progression

The goal is to increase reps achieved across all sets with a given weight before increasing load.

For example, the program calls for Squats 3x8-12:

Week 1:

Set 1 – 100x10; Set 2 – 100x9; Set 3 – 100x8

Week 2:

Set 1 – 100x11; Set 2 – 100x10; Set 3 – 100x9

Week 3:

Set 1 – 100x12; Set 2 – 100x11; Set 3 – 100x10

Typically, this would be followed until you hit the end of a given rep range and then you would add weight and allow reps to fall back down, thus repeating the process over again. In this example, we would progress to 105 lbs. since 12 reps at 100 lbs. was achieved.

Triple Progression

The goal is to increase reps achieved across at least one set with a given weight before increasing load.

For example, the program calls for Squats 3x8-12:

Week 1:

Set 1 – 100x10; Set 2 – 100x9; Set 3 – 100x8

Week 2:

Set 1 – 100x11; Set 2 – 100x9; Set 3 – 100x8

Week 3:

Set 1 – 110x11; Set 2 – 100x10; Set 3 – 100x8

Typically, this would be followed until you hit the top end of a given rep range ON ALL SETS and then you would add weight and allow steps to fall back down to the bottom of the rep range thus repeating the process over again. In this example, we would continue until we hit 3x12 with 100 lbs., and then move up to 105 lbs. and start progression over. Once we achieve 3x12 with 105 lbs., then we can increase to 110 lbs.

Volume Progression

The goal is to increase the number of sets performed each week or across a mesocycle for a given exercise.

For example, the program calls for Squats 3x8-12:

Week 1:

Set 1 – 100x10; Set 2 – 100x9

Week 2:

Set 1 – 100x11; Set 2 – 100x9; Set 3 – 100x8

Week 3:

Set 1 – 100x11; Set 2 – 100x10; Set 3 – 100x8; Set 4 – 100x7

Typically, this would also be done in conjunction with load/rep progression (i.e. linear, double, or triple). Increases in volume will be more regulated based on recovery week-to-week (rather than explicitly pre-programmed) and generally should be left for intermediate/advanced athletes. Caution should be taken with this progression method as volume increases (i.e. number of sets) tend to generate more fatigue than increases in loads or reps.

Technical Progression

The goal is to increase proficiency with exercise technique and movement quality.

For example, the program calls for Squats 3x8-12:

Week 1:

Poor ROM; excessive butt wink; excessive knee valgus

Week 2:

Corrections made to the ROM and valgus issues

Week 3:

Corrections made to butt wink

Typically, this will be more applicable with exercises that have higher skill requirements such as squats and deadlifts, but it should be used liberally when safe execution or proper ROM are a concern/limitation.

Because tracking improvements in technique and ROM are not as clear as quantitative progressions, it is strongly encouraged that you record your sets in order to validate this method.

Neurological Progression

The goal is to increase ability to voluntarily contract a muscle as well as the strength of that perception of tension.

For example, the program calls for Squats 3x8-12:

Week 1:

Systemically fatiguing; lungs are limiting factor

Week 2:

Can now feel tension in glutes and quads during the sets; local fatigue in target muscles

Week 3:

Glutes and quads are engaged and bearing the full tension throughout the entire ROM; failure point comes from fatigue in target muscles

Typically, this will be a secondary method of progression and confined to movements/situations that are not intended to drive hypertrophic stimulus (i.e., accessory volume) because of the difficulty with objectively tracking improvements.

This progression model should support the other (more direct) models.

Modifying the Plan

While we advice being diligent in your preparation, things do not always go according to plan in practice — that’s OK and should be expected!

In saying that, we can actually create an action plan for how to handle the unexpected when it inevitably occurs…

Injury/Pain

Pain and discomfort are unfortunate parts of exercise which become even more apparent the longer and more seriously you perform the endeavor. But despite the unavoidable presence of aches/pains, there is a threshold that — if exceeded — should lead to immediate program changes to prevent exacerbating the issue. Once it is determined that a modification needs to be made, we recommend trying to stay as close to the intent of original prescription while staying under the pain threshold.

Evaluate the severity of the injury, and modify your subsequent sessions around it. If you are limited by a particular movement or experience above-threshold pain multiple sessions in a row, larger scale changes to the program may need to be made.

Example 1:

You are programmed Squats- 3x8-12 but your knees are really painful at the very bottom of the ROM, so you switch to Box Squats- 3x8-12 and set the box height just above the paint point.

Example 2:

You are programmed Squats- 3x8-12 but your low back is really bothering you from bearing the load, so you switch to Goblet Squats- 3x10-15 and slow the tempo down.

Unavailable Equipment

There will always be times that certain machines or equipment will be out-of-order or unavailable for use while you are at the gym. This will require making a modification. In these situations, we ask that you do your best in replicating the intent of the movement with another piece of equipment.

This will generally be more common on machines and cable due to the fact that not all machines and cables have the same parameters of loading even if they appear similar. Sometimes, even the exact same machines can feel different due to manufacturing discrepancies and wear-and-tear.

Example 1:

You are programmed Smith Squats- 3x8-12 but the Smith Machine is broken, so you make the decision to switch to High Bar Squats- 3x8-12.

Example 2:

You are programmed Seated Hamstring Curls- 3x10-15 but the machine is broken, so you switch to Lying Hamstring Curls- 3x10-15.

Changing Order of Exercises

If you frequently have to train at a busy gym or one with limited equipment, there is a high probability that you will have to wait to perform an exercise. Sometimes you will be forced to ditch the programmed exercise order and come back when the equipment is free, or modify with another variation that replicates the original intent; however, we recommend that you deviate from prescription as little as possible.

It is important to understand that changing the order of the movements will impact your ability to generate intensity and the load you’re able to use, so previous weeks’ performances won’t have as much relevance in the modified session.

Example 1:

You are programmed Squats- 3x8-12, but all of the racks are taken so you move on to the next movement of the day which is Leg Press 3x10-15 and come back to squats immediately after.

Example 2:

You are programmed Standing Calf Raises- 3x8-12, but the machine is taken. You determine you can perform the rest of the session then come back to the calf raises at the very end because it is lower on your priority list compared to the other movements.

Short on Time

Inevitably, there is going to be a time when you are at the gym and life calls you away for whatever reason. Remaining calm and having a game-plan is paramount for these instances. Once it is determined that a modification needs to be made, we recommend prioritizing movements and performing them as prescribed until you have to leave.

There are many different ways that we can go about this modification, but it is crucial to stick to the program as closely as possible for long-term progression. Depending on the set-up of the split, you may be able to add in some of the work that was skipped on another day during the same training week as long as it is done intelligently and doesn’t impair recovery for the next sessions.

Example 1:

You get a call halfway through your session and have to be at work in an hour, so you look ahead and determine that squats, RDLs, and leg extensions are the order of priority so you continue in the order as planned until you have to leave.

Example 2:

You arrive to the gym knowing that you only have 45 minutes to dedicate to the workout, so you prioritize squats, RDLs, walking lunges, seated hamstring curls, standing calf raises, and leg extensions in that order. You only get through squats and RDLs before having to leave.

Bad Workouts

Having occasional bad workout is just part of the deal with taking training seriously and being an athlete. And the longer you train, the more frequent those less-than-stellar sessions become.

Bad can be defined in various ways but for the sake of this modification, we are going to use it to describe drastically decreased biofeedback markers when compared to the norm. Once it is determined that a modification needs to be made based on poor biofeedback, we recommend isolating the variable with the greatest negative impact and reducing the session’s reliance on it (through as little modification as possible).

This should be an absolute last resort. Exhaust all other resources and efforts before having to modify based on a bad workout. This is NOT an excuse to leave the gym out of frustration.

Example 1:

You only had 3 hours of sleep the previous night and little food before your session, so your energy is very low. You attempt to work around this by acutely (single session) reducing the set volume to ensure the work you are able to do is as productive as possible.

Example 2:

You are in a caloric deficit and just had a large macro drop so your strength is taking a hit. You attempt to work around this by acutely (single session) reducing the load you are using in order to more easily get the prescribed volume in without exceeding the prescribed proximity to failure.

Different Gyms/Equipment

Trying to perform the same session (in terms of exercise selection and loading parameters) at different gyms with different equipment than what you’re accustomed to will often require you to make modifications. Change your session as little as possible in terms of exercise selection and attempt to continue with the prescribed progressions where you are able.

We highly recommend sticking to the same gym for every week of the same session within a mesocycle (though you can vary gyms more liberally within your training week). If you do have to deviate, make intelligent weight selections within the loading parameters and intent guidelines of the original prescription to continue getting the desired effects.

Example 1:

You are traveling for work and have to modify all of machine and cable-based exercises because of the different brands between the gyms. You continue following your progressions on your barbell and dumbbell movements for the week but change the machine and cable work based on the rep ranges and intensities you are meant to be working in. In addition, the gym you trained at while out of town did not have a hack squat (which was programmed), so you did Smith machine squats instead.

Example 2:

You have to rotate between two different gyms based on your schedule and end up needing to perform the same session at each gym multiple times during the mesocycle. You still aim to follow progressions on barbell and dumbbell-based movements, but modify the other variants as needed and, taking prior knowledge of your strength on those familiar pieces of equipment, implement a realistic progression model for them.

Intentional and Unprogrammed Rest Days

There will be times when you have to make an intelligent decision to take an unplanned rest day (or two) because of incomplete recovery from prior sessions.

There is nothing wrong with taking rest days when your body needs it, but we highly advise being honest and realistic with yourself here. It is more beneficial to space your training out with additional rest days to improve the quality of each sessions than trying to training through fatigue and under-recovery.

Example 1:

You trained quads on Monday and are supposed to train them again on Thursday with a high volume and intensity, but they are still very sore from the last session. Instead, you take an extra rest day to give the soreness more time to dissipate and then train quads hard again on Friday.

Example 2:

You had an extremely taxing leg work-out on Saturday, and it is the 6th week of this progression. You are programmed to train back hard on Sunday, but you are still completely exhausted from the leg session, so you move the back session to Monday to allow yourself a bit more time to eat, sleep, and rest.

Unintentional and Unprogrammed Rest Days

There will be times when life just happens: work, family emergencies, not feeling well, etc. We urge you to prioritize those situations before getting back to the gym.

Depending on your responsibilities and how reliant others are on you, this may be a very rare occurrence or something that must be addressed frequently. We will never be able to periodize training around emergencies and random life events, but we can always do our best to be pragmatic so that we are put in the best position possible to succeed.

Example 1:

You have a very important project at work and the deadline for completion is approaching quickly. Instead of trying to poorly fit your scheduled training into an already time-crunched week, it may be prudent to take a few rest days and just focus on getting your work done.

Example 2:

You find out suddenly that your father, who lives far away from any gyms, needs surgery and will need someone to care for him while he is recovering. A week or so away from the gym to take on this responsibility and ensure everything is tended to will not ruin your progress.

Plateaus and Setbacks

Much like acute modifications to the plan are inevitable, so too are generalized hindrances to progressive training. Ideally, we’d like to minimize the occurance of large-scale programming dislocations through intelligent training and planning, but this won’t be enough in every instance. So we should have a plan in place for how to manage some common sources of setbacks and plateaus.

Injury

Acute injuries, such as muscle strains, are less likely than you might think, and catastrophic weight room injuries are very rare. You can avoid the vast majority of injuries, aches, and pains by lifting with good technique and adhering to a strategic progression model.

However, if you do sustain an injury or flare up an old one, is important to note two things:

Muscles heal relatively quickly, and you will regain all of your old size/strength (and then some) as soon as you get back to training at full capacity.

Injuries will rarely require you to fully stop training. Training through an injury is reckless, but there are almost always ways to safely train around it. You may even be able to perform the same movement that you injured yourself on, albeit with a modified load, tempo, and/or ROM.

Don’t be dumb when attempting to recovery from an injury, but being aggressive in your rehab (up to a limit) can facilitate much faster recovery compared to doing nothing.

Sickness

No matter how proactive we are, eventually we all succumb to some illness, virus, or bug. Severity and infectiousness will dictate your ability to train, but it is almost always better to stay home until you have recovered instead of trying to train through it and potentially make yourself sicker and/or infect others.

Symptoms that should deter you from training:

Fever

Body aches/chills

Diarrhea

Vomiting

Severe muscle spasms

Severe migraines

Symptoms that can be trained through in moderation:

Headache

Congestion

Sore throat

Sinus issues due to allergies

Consistently Poor Biofeedback

If you have multiple poor performances in a row — say a whole week or two of workouts where you feel overly fatigued or sore — then something probably needs to be changed. You may need a week or two of lighter training (refer to Deloading section) or reduce your workload so you can recover better.

One bad workout is not a cause for concern, especially when precipitated by acute poor sleep, missed meals, or an especially stressful day. As we have emphasized, improving your physique and performance is a long-term process, and one session means little in comparison to months of consistency and hard work.

Missing Workouts

Just as one bad workout means little in the grand scheme of things, missing one workout will not set you back. If it happens, be honest with yourself and transparent with your coach (if you have one). The short-term action plan may be to keep the rest of the week’s workouts exactly the same, or it may be prudent to adjust your training schedule in order to get in some of the important work from the missed session.

If missing workouts becomes a common occurrence, it would then be necessary to make a change. Fewer weekly workouts — done consistently — will always beat a sporadic completion rate. Your program should be designed to emphasize a specific progression model (refer to Progression Models), so if you feel your schedule becoming more unpredictable, make the necessary adjustments preemptively in order to maintain the spirit of that emphasis.

Stalled Progress

What people often think of as plateaus are more often the result of unrealistic expectations of never-ending, rapid progress. There may be times when your performance or physical appearance seems to change rapidly, but by-and-large, gaining strength is a long-term process. And growing new muscle tissue is even slower. Fat loss can happen relatively quickly, but even then, the scale and mirror may not always reflect that progress on a daily basis.

If you feel that your progress has stalled for a few weeks, let your coach know (if you have one). They may be able to point out plenty of areas where you have made progress; but if need be, they can also make necessary adjustments to your training program and/or diet. If you don’t have a coach, look to trends in your performance data and biofeedback markers for a more accurate distinction between slowed progress and stalled progress. The former implies that the plan is still working, while the latter indicates that some change should most likely be made.

Recovery Strategies

Recovery from training is paramount; without it, no progress can happen. So taking recovery seriously — and implementing effective strategies to improve it — can be one of the most impactful things you can do when trying to get jacked and strong.

Caloric Balance

Nutrition is going to be the biggest determinant of how well you can recover, outside of the training itself. Being in a deficit or having an inconsistent eating schedule will limit the resources available that are needed to heal from hard, voluminous training. Conversely, eating in a modest surplus (but not like a glutton) will provide our systems with essential calories (energy for physiological processes) with room to spare so that our muscles and soft tissues can go through the full recovery process properly.

Sleep

There is plenty of evidence to support the idea that chronic sleep deprivation is one of the worst things we can do to ourselves if we expect to be able to train hard and recover from that hard training. Tons of essential processes happen while we sleep including hormone production, autonomic nervous system regulation, maintenance of immune function, and plenty more. As little as one or two acute instances of poor sleep can negatively affect training, but a consistent lack of quality sleep (not just the number of hours in bed) can quickly push us towards overreaching. Prioritizing getting at least 7-9 hours of sleep per night — along with practicing proper sleep hygiene — can make a world of a difference towards our recovery.

Stress Management

We now understand that our bodies do not necessarily treat physical stressors (i.e., training) much differently from emotional and psychological stressors (i.e., getting fired from your job or broken up with by your significant other), and a lot of the physiological responses to seemingly unique stressors are actually the same. What this means is that it is imperative that we are able to rest and relax and “turn off” the stresses that come with daily living if we expect to be the best version of ourselves in the gym. Setting aside time for stress-management strategies like casual social gatherings, relaxing massages, controlled breathing exercises, yoga, and even semi-frequent “intimate time” can greatly improve our ability to recovery (albeit indirectly).

Light Cardio

Low intensity steady state (LISS) cardio can be a great way to not only increase energy expenditure and burn fat, but also as a route towards decreasing fatigue and pushing nourishing blood into afflicted tissues. However, there is a fine line here when it comes to dose — as measured in time and intensity — so we recommend using LISS as a recovery strategy with caution.

Foam Rolling

Though foam rolling can be great for acutely allowing increases in flexibility and mobility — if done pre-workout, for example — it is not going to be a significant factor in recovering from hard training. We recommend using foam-rolling sparingly as a recovery strategy.

Stretching

Like foam rolling, we can see increases in flexibility and mobility from stretching, as well as possible decreases in delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) if used strategically as part of a cool down. But overuse of stretching — static and especially dynamic — can actually cause MORE fatigue and thus impair recovery from training. We recommend utilizing moderate-intensity stretching post-workout on warm muscles, and limiting the volume/frequency in order to get the beneficial effects without pushing into deleterious territory.

Cold Therapy

Icing has been used for decades as a way to decrease the perception of local pain/swelling after activity, However, it is important to understand that targeted cold therapy is doing very little for aiding in systemic recovery, though managing local inflammation can allow for reduced time to regain full fitness after an overloading bout.

Full-body immersion (i.e. cold plunges) does seem to have some support in the research — especially when it comes to management of hormonal markers of stress — though, the ideal application and dose seem to be somewhat hard to pin down. Accordingly, it’s difficult for us to give a confident and safe recommendation that optimizes for recovery while managing the potential serious consequences of misuse.

An additional consideration would be that cold acts as vasoconstrictor (reduces blood flow) so it is best utilized on achy joints or acute swelling to manage pain and inflammation. Putting ice on sore muscles is generally contraindicated and may actually lengthen recovery time.

Heat Therapy

In contrast to the cold, heat therapy benefits from acting as a vasodilator and is best used to promote nutrient-dense blood flow into sore muscles and carry-away intracellular waste products. This method has more applicability for aiding in acute recovery from DOMS but does little for decreasing pain and inflammation (like cold therapy).

Contrast Therapy

This is when you use cold and heat to bring about the desired beneficial effects of both. Typically, this would be done using large baths of ice water and warm water; you would then alternate back and forth to (hopefully) induce a systemic reduction of fatigue and increased recovery.

When done in proper dosing and with intelligent protocols, this can be a phenomenal way of dissipating local fatigue, although it is unclear how to balance this pro with the obvious con of an increased stress response due to the shock of changing temperatures.

Because most people do not have access to this type of contrast therapy, the method can be replicated on a more-targeted level with hot and cold packs.

Deloading

A deload is a period, typically one training week but can be as short as 3-4 days, where the goal is to reduce systemic and local fatigue through reductions in volume, intensity, and relative load. Deloads are implemented after the culmination of a hard mesocycle and are meant to prepare you physically and psychologically for the next phase of training.

When to Deload

Excessive DOMS

When soreness indicators are becoming excessive and persistent after bouts of training, it is generally a sign that recovery capacity has been exceeded. A deload is then needed to wash the fatigue out before attempting to push back up again.

Performance plateau or regression

The goal of overloading training is quite literally meant to overload or do more than the last bout. Doing this frequently and long enough will add up to more muscle growth. However, this is not sustainable indefinitely. At some point, we will experience a halt in progress, and in some cases, we will see performance markers actually go backwards if fatigue is high enough and remains unaddressed. If this is a trend for two weeks in a row across multiple sessions, it is time to deload.

Chronic sickness

This should go without saying but having a sickness or ailment that just “won’t go away” is a very clear sign of compromised immune function, and one of the biggest contributors to this is the compounding of hard training.

Random stomach bugs and head colds are inevitable but if you find yourself constantly struggling to kick even the simplest of symptoms (like a cough), it may be time to pull back on training for a bit and allow your body time to fully recover.

Aches and pains

To a degree, this is going to be unavoidable when you are training hard no matter how intelligent you go about programming and planning, but the accumulation of achy joints and strained muscles can be a clear indication that too much of something is being done and not enough of everything else is being done to counteract that training.

If you find yourself sustaining nagging injuries at an accelerated rate, think about tapping the breaks for a bit and allowing those to heal before become chronic issues.

Life events and travel

Training is always secondary to enjoying life even for the most serious competitors. With enough time, events/obligations will be scheduled that necessitate a leave of absence from the gym.

If we have some forewarning, we should be able to plan our training to crescendo right before the leave in order to use this event/travel/vacation as a natural deload.

How to Deload

Combined reduction

This will be the method that is most effective for dropping accumulated fatigue while maintaining training qualities (like technical aptitude) and stimulating further recovery through increased blood flow.

For this, we recommend tapering volume significantly (by ~40-50%) and intensity moderately (by ~25-30%) from the last overloading week before implementing the deload. For example:

Week 1:

Squats 2x8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2:

Squats 3x8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3:

Squats 4x8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4:

Squats 5x8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload:

Squats 3x7 with 80lbs

Load reduction

Though load on the bar is still a distance behind volume when it comes to fatigue generation, combining high relative loads (as a % of 1RM) with high intensities (as a proximity to failure) will put a ton of stress on our recovery systems.

When most people talk about deloading, they are typically referring to the load reduction method because “lighter” is used as a blanket term for many deloading strategies. For example:

Week 1:

Squats 2x8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2:

Squats 3x8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3:

Squats 4x8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4:

Squats 5x8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload:

Squats 5x8 with 50lbs

Volume reduction

Volume will be the biggest contributor to fatigue, so it should generally be the variable that we attack first to reduce it.

This can be done through a reduction in total sets, reps per set, or a combination of both. For example:

Week 1:

Squats 2x8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2:

Squats 3x8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3:

Squats 4x8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4:

Squats 5x8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload:

Squats 3x5 with 100lbs

Modified hypertrophic

Though the combined reduction of volume and load leads to the best specific outcomes with regards to dropping fatigue and increasing preparedness for the next mesocycle, employing what we call a modified hypertrophic deload typically leads to better long-term outcomes when the goal is STRICTLY muscle gain.

This method still leans into decreases in volume and load to drive the recovery process but with the added element of increased voluntary contractions. In other words, we want to focus more heavily on emphasizing the mind-muscle connection now that intensity is no longer being prioritized. For example:

Week 1:

Hip Thrusts 2x8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2:

Hip Thrusts 3x8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3:

Hip Thrusts 4x8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4:

Hip Thrusts 5x8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload:

Hip Thrusts 4x6 but the weight is autonomously chosen so that the athlete can perform the movement with the best execution and greatest perception of sensation in the glutes.

Time off

This would be a period of completely taking off from direct strength training.

Low intensity cardio can still be performed (and is recommended) but it is advised to stay away from the gym as much as possible during planned time off to accommodate psychological (burnout) as well as physical recovery.

We do not recommend this more frequently than 2-3 times a year, but implementing at least one consecutive 7–10 day stretch of active rest is probably a very good idea on occasion. Bonus points if you can align this with vacation!

What’s Next?

Assess Progress

Before we can decide how to move forward with our training, we must be able to objectively look at how well we progressed during the previous mesocycle. We need to be able to filter what worked well (and can potentially remain in the program) from what was a flop (and needs to be replaced ASAP).

It is crucial to look at quantitative data — such as reps achieved and loads used — to track how well we are utilizing progressive overload to drive our muscle/strength gains. Additionally, we should be evaluating qualitative data — such as measures of biofeedback — to add context and see if they validate or contradict the quantitative story.

This process should be pulling data from not just the preceding training but also from the accumulation of information that we have hopefully been tracking for months, if not years.

Run It Back

If you noticed positive trends in BOTH objective and subjective feedback for a particular exercise, rep scheme, intensity range, etc., then it may be beneficial to continue with the same prescription into the next phase and milk it for all the progress you can get.

Remember: do NOT start off your new training where you ended the last overloading week before the deload, otherwise you will hit your ceiling much too early. Instead, plan accordingly and pull back in load/reps just enough so that you set yourself up for a PR (by whichever metric you’re measuring) by the END of the next mesocycle.

Modify

If either the numbers (in terms of load and sets/reps) OR the biofeedback (in terms of perception of effort, MMC, injury potential, etc.) paint a negative picture when evaluating the last mesocycle, something definitely needs to change. The modification will generally be based on which aspect of the data was limiting.

When making changes to an exercise variation/order, loading/rep scheme, etc., it is generally advised to NOT completely overhaul your training. We should always be building a complete picture of what works for us as an individual — versus what clearly does not — and this means holding onto some degree of consistency in all of our subsequent training blocks.

Example 1:

You have chronically poor knee health that is exacerbated by heavy squatting/lunging movements, but leg pressing feels great and provides an ideal stimulus compared to the cost of injury/fatigue. It would probably be a good idea for you to keep some kind of leg press variation in your training at all times and build around this movement, so you can stay healthy and avoid further knee issues.

Example 2:

You find that performing leg press with very high load and quad-focused set-up (low foot placement) bothers the knees. Rather than completely moving away from leg pressing, you instead alter the rep range, tempo, and foot position to alleviate the problem and allow yourself to continue progressing.

Beginning the Next Phase

When starting your new mesocycle, you will have experienced a slight reduction in fitness from your deload so it’s a good idea to begin the first training week conservatively in volume, load, and intensity. Use knowledge of prior performances to estimate loads for the given rep ranges/intensities. If you are performing a new movement, rep scheme, exercise order, and/or intensity technique, use your best guess and adjust as necessary in the succeeding weeks. However, it is always better to err on the side of too conservative and leave ample room for progression rather than setting yourself up for failure by overdoing it right out of the gate.

Appendix

Further Reading

What to Expect When Hiring a Coach

Everything You Need to Know About Failure

Inventory of Intensity Techniques

Exercise Variability—Why, When, and How to Use Novel Exercises

Anatomy and Biomechanics

Skeletal System

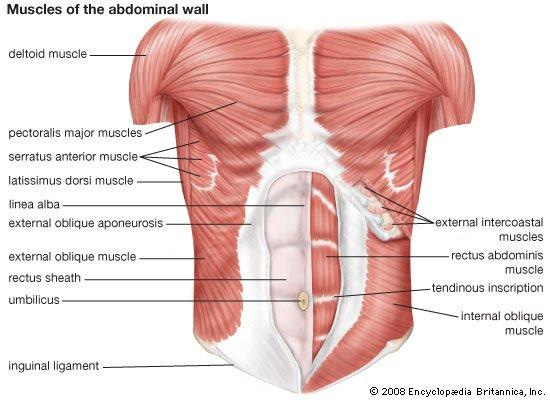

Muscular System (Anterior View)

Muscular System (Posterior View)

Muscles of the Back

Abdominal Muscle Complex

Anteroir Leg Muscles

Posterior Leg Muscles

Pectoral Muscles

Biceps Muscles

The Nervous System

Planes of Motion

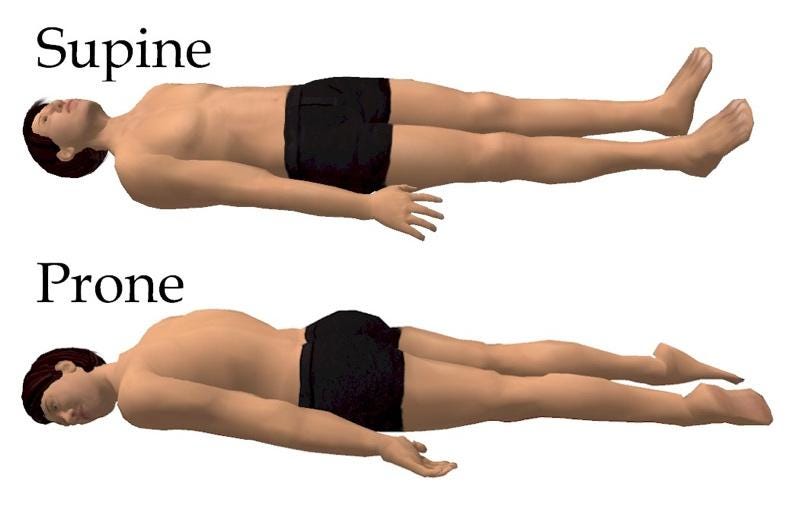

Anatomical Positions

Movement of Joints

DISCLAIMER: Bryce Calvin is not a doctor or registered dietitian. The contents of this document should not be taken as medical advice. It is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any health problem - nor is it intended to replace the advice of a physician. Consult your physician on matters regarding your health. Materials in email transactions are not to be shared.